“This was a matter I decided in the space of three puffs on a cigarette.”

So said the Japanese General Miura Gorō of his decision to assassinate Queen Min of Korea.

The Japanese had sought to influence Korean affairs with varying degrees of success for centuries prior to the events of 8th October 1895.

In the months leading up to the assassination, Japan fought China for control over Korea in the first Sino-Japanese War.

Japan's interest in Korea was strategic. The Korean Peninsula served as a buffer zone between Japan and its main rival, China. Moreover, Korea's geographic proximity to Japan made it a crucial link in Japan's expansionist ambitions in East Asia. As Japan modernised and industrialised in the late 19th century, it sought to assert its dominance over Korea to secure its own geopolitical interests.

Japan had already won Korea from China, it did not need to assert its control in the manner Miura Gorō chose.

Queen Min's resistance to Japanese encroachment stemmed from her commitment to preserving Korean sovereignty and independence. She recognised the threat posed by Japan's expansionist ambitions and sought to counterbalance Japanese influence by fostering closer ties with Russia.

In the late 19th century, East Asia was a main area of focus for a great many countries seeking to expand their spheres of influence. Japan, with its modernised military and aggressive foreign policy, and Russia seeking to establish a foothold in East Asia with Korea as an ideal location for warm water ports. The English, French and Germans were all active in the region, too.

Queen Min's efforts to align Korea with Russia and resist Japanese influence incurred the wrath of the more hawkish Japanese officials who saw her as an obstacle to their expansionist agenda.

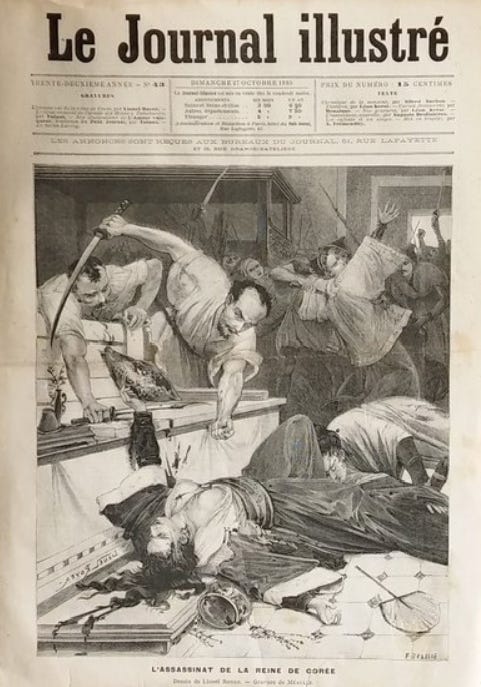

In 1895, a group of Japanese assassins, acting on orders from General Miura Gorō, infiltrated the royal palace and brutally murdered Queen Min.

With her death, Japan effectively gained control over Korea's foreign policy and internal affairs with the Treaty of Shimonoseki paving the way for its eventual annexation of the peninsula in 1910. The remnants of the Korean royal court sought refuge in the Russian legation. The Korean people’s sympathies were with the royal family, Russia’s influence grew significantly. As a political assassination, that of Queen Min backfired greatly, with the people granting her the status of "Empress Myeongseong" posthumously.

Japan’s enmity with Russia which had commenced with the Tsushima incident of 1861 had just escalated a significant notch.

Manchuria was another region in which Japan and Russia were competing for dominance, although the Germans were really upsetting the natives. Killing those who protested the building of a railway was never going to win hearts and minds. The Boxer Rebellion in 1900 in which a Chinese tribe versed in martial arts (hence the ‘boxer’ epithet) sought to expel foreign powers carving up the region, raised the temperature further.

By 1905 Japan and Russia were involved in a full-blown war, a war in which Russia was soundly defeated.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1905 was expensive for Russia in money, in lives, and politically, in that it weakened the Tsar’s legitimacy as absolute monarch. The war, coupled with the socioeconomic hardships endured by the Russian populace, created fertile ground for political dissent. It was amidst this backdrop of disillusionment and unrest that Marxism gained traction as a revolutionary ideology promising liberation from oppression and exploitation.

The writings of Marx had attracted the attention of scholars and dissidents, however for it to succeed as an ideology beyond academia and trade unionism it needed a country-sized petri dish.

World War I, further destabilised Russia and precipitated the collapse of the Romanov dynasty. The February Revolution of 1917 ushered in a period of political upheaval, culminating in the Bolshevik seizure of power in October of the same year. Led by Vladimir Lenin and inspired by Marxist principles, the Bolsheviks established the world's first socialist state, fundamentally altering the course of history.

Despite the socialist experiment in Russia being an abject failure by any measure, its one success (if it can be called that) was outside its borders. The ideology behind socialism was exported worldwide. Idealists lapped it up. Even the Communists called these credulous souls “useful idiots”.

The Soviet Union, under Lenin's successor Joseph Stalin, sought to export communist ideology and extend its influence beyond its borders. The KGB, the Soviet Union's notorious intelligence agency, played a pivotal role in this endeavour, employing covert tactics to promote communist revolutionaries and undermine capitalist regimes around the world.

The testimony of Yuri Bezmenov, a former KGB agent turned defector, offers insights into the clandestine efforts of the Soviet Union to advance Marxist-Leninist ideology globally. Bezmenov's accounts reveal the extent to which the KGB manipulated political movements, fomented unrest, and disseminated propaganda to further Soviet interests.

The Eastern Bloc political alliance controlled by the Soviet Union might have been broken up at the conclusion of the Cold War in 1989, but it cannot be said that the war was ‘won’ by the west. Russia might have moved from soviet socialism to authoritarian dictatorship, but just about every Western country is now paralysed by excessive socialism.

The key word here is ‘excessive’. Few would be so cold as to deny the basic principle of “to each according to their need”, however the concept of ‘need’ seems to have expanded gradually up Maslow’s pyramid such that the wants of party members exceed the capacity of society to pay for them. No longer do we restrict the role of the state to supplying the basics of food, education and security to those who cannot provide for themselves. Now the state has to control your self-actualisation.

That which was cultivated in a petri dish in Russia has escaped the laboratory and become a global pandemic.

Would Tsar Nicholas have succeeded in turning Russia into a constitutional monarchy along the lines of that of the United Kingdom had he not had his political capital wrenched from him by the Japanese?

Would Japan’s enmity with Russia have been lessened or been resolvable had General Miura Gorō taken a few more puffs on his cigarette, and concluded that a bloody despatch of Korea’s Queen was not such a great idea?

Who knows?

But when people ask me how we got here, I tell them: “Japanese General Miura Gorō took three puffs on his cigarette”. It’s as good a story as any.